TRAGEDY STRIKES

NORMANBY FAMILY

Researched by; Mrs Beverley Barker.

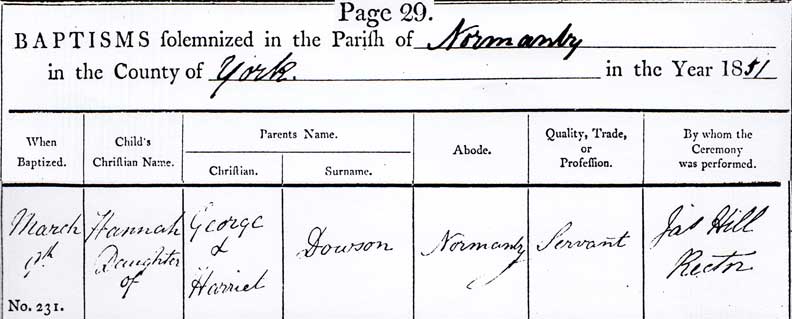

Hannah Dowson was born in Normanby in

1851, the third of seven children of George Dowson and Harriet Boyes. She

was baptised at St Andrews Church, Normanby on the 9th of March, 1851.

|

Her father, George was employed as a groom, gardener, and fruit dealer

over the decades, but by 1881, he was a publican, running the Fox & Hounds

at Sinnington. He was born in 1821 in Great Barugh and died on the 14th

of March, 1898 in Kirkby Moorside. Harriet was born in Hutton Le Hole on

the 10th of October 1819, and died on 20 Mar 1868 in Normanby.

While researching my husbands’ family

history, we found George & Harriet's’ gravestone in St Andrews churchyard, and this led us to discover the tragic fate of their daughter, Hannah

(who

was my husbands first cousin, four times removed).

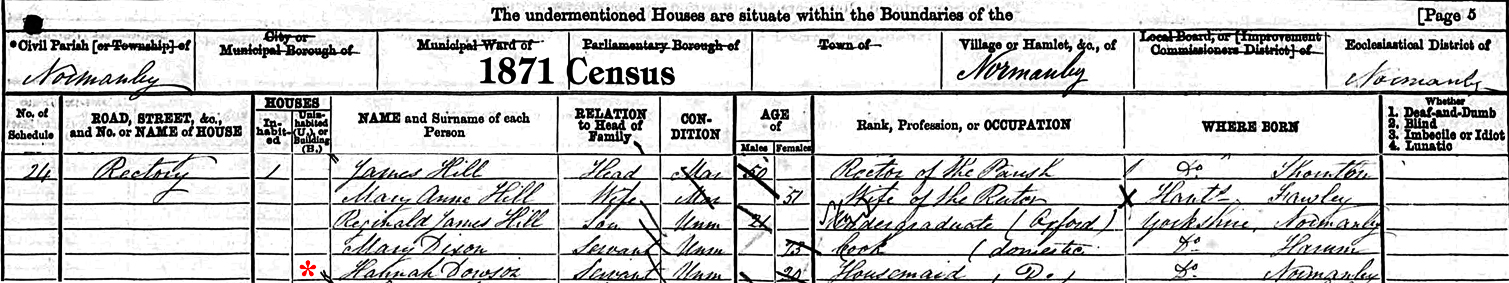

Hannah grew up in Normanby, went to

school, and in 1871 she was working as a housemaid at Normanby Rectory.

Her mother died in 1868, and her father George remarried.

|

Fox & Hounds Sinnington c.1900 |

|

1871 Census Normanby Rectory |

|

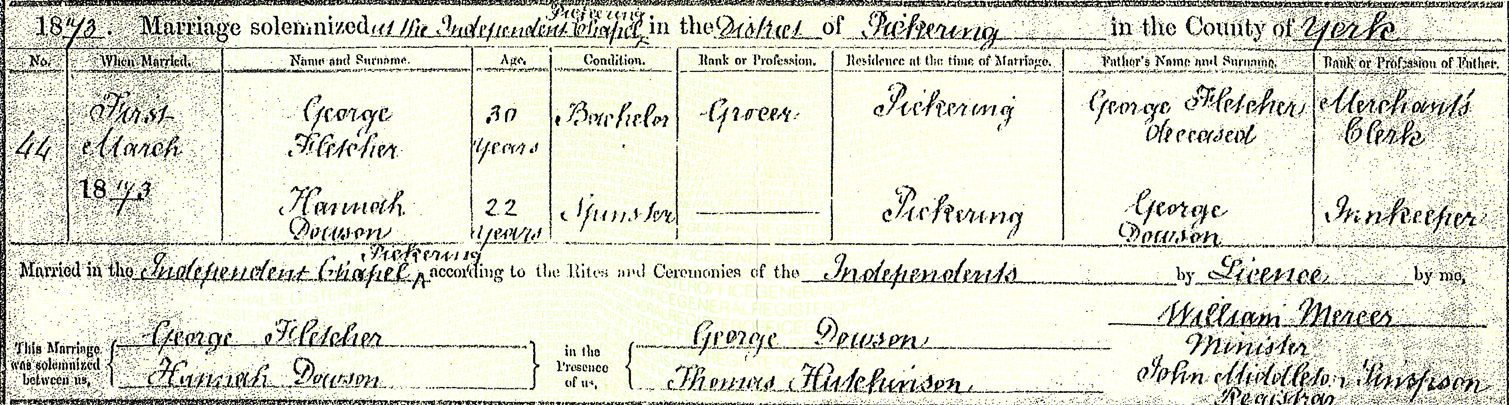

On March 1st, 1873, at the age of 22,

Hannah married George Fletcher, a grocer from Burgate in Pickering. He was

the 3rd of five children of George Fletcher (a merchants’ clerk) and

Elizabeth Lynas, and was baptised in Pickering on 29 May 1842, He was 30

years old when they married.

George Fletcher & Hannah Dowson

Marriage 1873 |

I believe that George had purchased

some land from the Burlington & Missouri Railroad Company in Lincoln,

Nebraska, USA for £100, and the newlyweds booked a passage on the SS

Atlantic at six guineas each (£6-6s) and were on their way to a new life.

The passage would

take eleven days

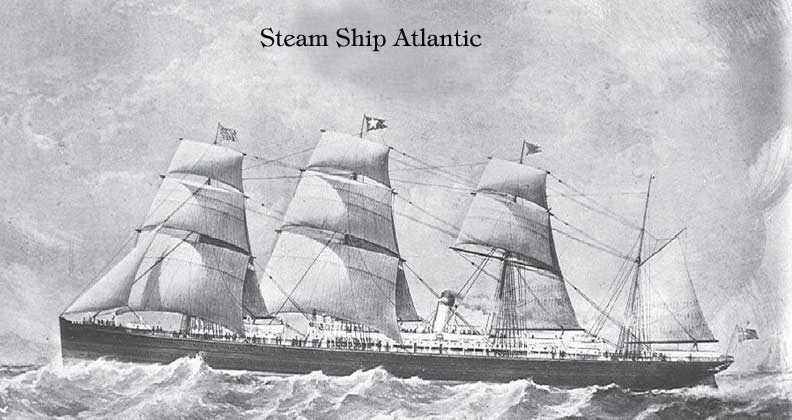

The SS Atlantic was built by

Harland &

Wolff in Belfast and was owned by the White Star Line. She was 420 ft

long, 40.9 ft wide and 32 ft deep. She was launched on November 26th,

1870, and was about to embark on her 19th Atlantic crossing when George

and Hannah boarded her in Liverpool. They sailed at 3.20pm on March 20th,

1873. The ship made good time and arrived at Queenstown (Now named Cobh)

in Ireland to collect more passengers, and at 1030am on 21st March, the

Atlantic was on her way to New York. There are conflicting reports of how

many passengers were on board; the Captain, James Agnew Williams stated

there were 976.

George and Hannah were travelling

steerage, in the married couples’ quarters. There were two decks for

emigrants, each 8 feet high. Their quarters were above sea level,

mid-ship, near the engine room. These quarters were dark and gloomy,

and they slept on wooden ‘shelves.’ There was little privacy, or

ventilation and The White Star Line provided no bedding. The only access

to and from their quarters was via a steep companion ladder. Most

steerage passengers would spend the days on deck to escape their

suffocating quarters. They were provided with 3 meals a day and each

passenger had a daily water allowance of 8 quarts.

For the first few days the ship

progressed normally, the weather was good. On March 25th, the weather

deteriorated, with gale force winds and building seas. The passengers

remained inside their quarters, most had seasickness. On the 27th, the

weather worsened further, with gales from the west. Lifeboat No 4 was

destroyed. The ship had weathered many storms as

this, but life below decks for George and Hannah would have been very

unpleasant indeed.

On March 28th, the Captain ordered that

coal should be conserved; the storm had slowed the ships’ speed to 5-8

knots, and he was concerned they would run out of coal before reaching New

York. By the 31st, there had been seven days

of storm conditions and at 1pm that day, the Captain decided they would

change course to Halifax, Nova Scotia to collect more coal. By changing

course, the Atlantic averaged 11 knots as the wind was now to port

(left). All was well, the passengers had a respite from the terrible

conditions and were quite excited about the unexpected stop-off.

Captain Williams went to his cabin for

a sleep and was asked to be woken at 3am, on the 1st of April, when he

expected the ships’ position to be at Sambro lighthouse, where they would

wait until daylight to negotiate the numerous rocky islands ahead of the

entrance to Halifax Harbour.

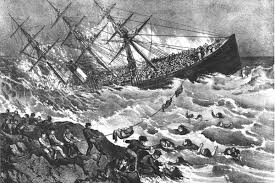

At 3.10am, nobody had woken the Captain

as the lighthouse was still not in sight. Unfortunately though, the ship

had veered off course; the Quartermaster spotted breakers and raised the

alarm, but the ship ploughed at full speed into an almost vertical cliff

of hard granite, about 100ft from Meaghers (Marr’s) Island. The stern

immediately began to sink. The Captain now fully roused, he ordered

everyone to the bow of the ship, that the lifeboats be readied and to

abandon ship. Flares were sent up. Within 10 minutes of grounding, the

ship lay on her side.

Below deck, hundreds of frantic

steerage passengers; no doubt including George and Hannah, were

desperately trying to climb the companion ladders, but as the water poured

in, the ladders collapsed and were useless.

All the single women in steerage died.

Of 167 families on board, with 116 children, only one child survived. Of

the 976 aboard, 546 souls were lost, including George and Hannah

Fletcher. They had been married for one month. The loss of the Atlantic

was the worst shipping disaster at sea for the White Star Line, superseded

only by the loss of the Titanic in 1912. Immediately following the wreck,

Captain Williams was on the bow of the ship with Third Officer Brady and

three Quartermasters.

Golden Rule Rock was about 25 yards

away from the sinking ship. It was low tide and the rock seemed a safer

option than staying aboard. After great difficulty and several perilous

swims back and forth, some of the men managed to run five ropes in the

pitch darkness from the ship to the rock. The passengers on the bow of the

ship used the rope as a guideline to reach the rock, and in time, there

were over 100 men on the rock. However, the tide was rising, and with each

crashing wave, many men were swept away into the freezing black water. The

bodies of dead women and children were being dashed against the rock; the

scene must have been absolutely horrific. As daylight broke, survivors still

clinging to the rigging of the ship made their way over. By now there were

hundreds stranded on Golden Rule Rock.

Third Officer Brady managed to get to

shore and came across a cottage owned by Michael Clancy. He had

already raised the alarm and had

despatched a local boy to row to the other islands nearby to fetch help.

Brady was followed by more survivors who had reached the cottage and Clancy’s daughter, Sarah Jane

cared for those who came, while Clancy and Brady returned to the shore

line. By now, space was running out on the rock and there were still

about 200 men on the hull of the Atlantic. Then hope came in the form of 3

local fishing boats. Captain Williams shouted from the hull that he would

pay £500 for every boatload saved if the men from the hull could be

rescued first. These three boats made repeated trips between the

wreck, the rock and the shore, rescuing about 400 in total.

Survivors made their way to the Clancy’s home, where Sarah Jane did what

she could to offer warmth and all the food and supplies they had to the

men.

survivors who had reached the cottage and Clancy’s daughter, Sarah Jane

cared for those who came, while Clancy and Brady returned to the shore

line. By now, space was running out on the rock and there were still

about 200 men on the hull of the Atlantic. Then hope came in the form of 3

local fishing boats. Captain Williams shouted from the hull that he would

pay £500 for every boatload saved if the men from the hull could be

rescued first. These three boats made repeated trips between the

wreck, the rock and the shore, rescuing about 400 in total.

Survivors made their way to the Clancy’s home, where Sarah Jane did what

she could to offer warmth and all the food and supplies they had to the

men.

By 9am all survivors had been rescued;

Captain Williams was one of the last. At about 5pm on the 1st, the

Atlantic broke in two, and yielded up those poor souls who had drowned

inside. As many corpses as could be were brought ashore and laid out.

Capt. Williams initially personally inspected every corpse; 180 in total.

Five identified saloon passengers were sent in coffins to Halifax to be

sent on to relatives.

It would have been a grim task to try

and identify the dead. Unfortunately it became apparent that the bodies

were being scavenged for valuables and Captain Williams had to appoint men

to guard the bodies. Some of the survivors, after resting,

decided to walk to Halifax that same afternoon. This trek took them 9

hours as there was a foot of snow in some places. Brady arrived there the

next day, organised a relief effort, alerted the authorities and Cunard,

the agents of the White Star Line in Halifax. Apparently, rumours had

abounded in Halifax of a disaster but were ignored as most people thought

it was an April Fool’s joke!

Steamers were sent to pick up the

survivors, who had been kindly cared for by other islanders. These men

were a bedraggled mixture of nationalities and social classes. From there

they went to Halifax then finally on to New York, their original

destination. Most had nothing as all luggage and personal belongings had

been lost. Eventually, hundreds of bodies were laid out on what was

termed the ‘Hill of Death.’ Debris and valuables from the wreck

site were scavenged and sightseers turned up to eat their picnics and have

their photographs taken at the scene of the disaster.

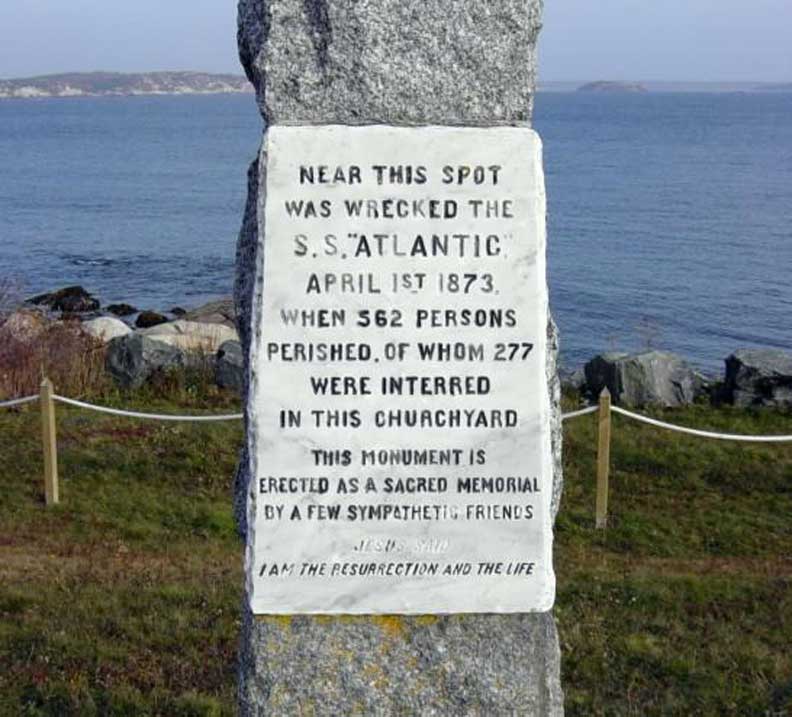

It was a massive task to undertake the

burials as there was almost no soil in which to bury the dead as the

islands were barren. The White Star Line sent a crew of gravediggers and

they dug two mass burial pits. 277 people were buried in the Anglican

graveyard at Sandy Cove, where there is a commemorative plaque (see

below). The other, which contained more than 150 people was at the Roman

Catholic Star of the Sea cemetery. A few others were buried around the

islands. I would like to believe that George and Hannah were found and

buried here.

The enquiry into the disaster began on

5th April 1873, and the conclusions announced on April 18th. The enquiry

deemed that there were five counts of improper management.

First, that the ship’s position was

further west than Capt Williams believed. This was caused by a westerly

current of which the Captain was not aware.

Second, that the ship must have been

sailing at 12 knots, and not 11 knots as had been allowed for. There was

incompetence in keeping the ship’s log.

Third, that Sambro Lighthouse must have

been visible yet not seen by the crew, and that a proper lookout should

have seen the rocks.

Fourth, that the fact that Capt

Williams went to bed, even while his ship was steaming at full speed in

the dark to an unknown coast, lulled his crew into a false sense of

security.

Fifth, that in the twelve hours before

the wreck, the lead was never thrown in to calculate the depth of the

water. This would have alerted the officers that they were not where they

thought they were.

Fifth, that in the twelve hours before

the wreck, the lead was never thrown in to calculate the depth of the

water. This would have alerted the officers that they were not where they

thought they were.

Capt Williams was however praised for

his ‘leadership and brave efforts in helping to save lives after the

wreck.’ He was given a penalty of having his Master’s License

suspended for two years. Not much of a penalty considering the

loss of life incurred by what was mainly human error.

http://www.ssatlantic.com/

“Near this spot was wrecked the S.S.

Atlantic. April 1st 1873, when 562 persons perished, of whom 277 were

interred in this churchyard. This monument is erected as a sacred memorial

by a few sympathetic friends.”

Information taken from various websites,

the Illustrated London News & Greg Cochkanoff’s book, ‘SS Atlantic, the

White Star Line’s First Disaster At Sea.’

©

Beverley Barker

Top